From the engine room to the court room – one stroke at a time

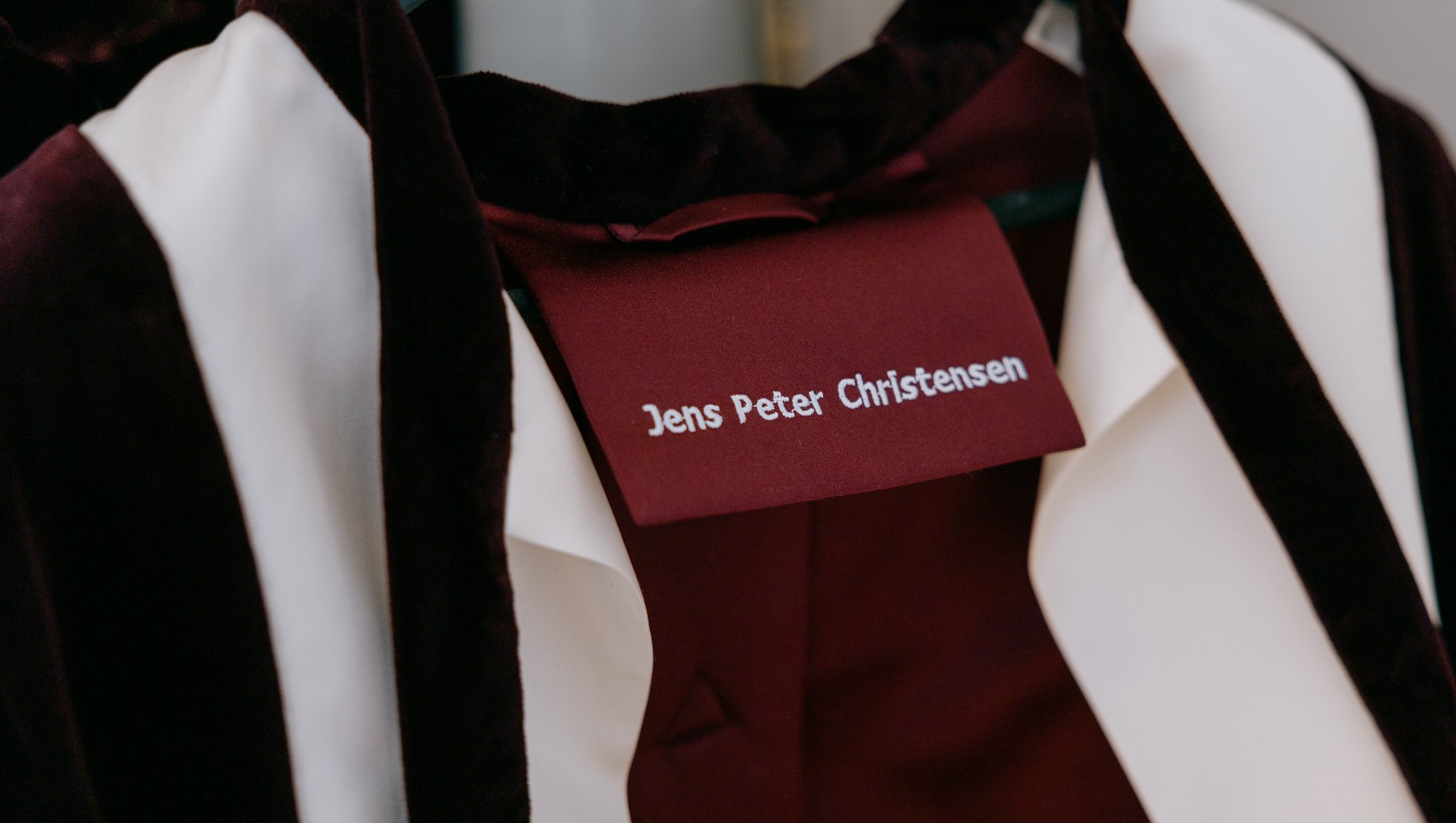

Jens Peter Christensen studied three different subjects before he applied for law. He was rejected at first, but the son of a stoker and World Championship rower from Jutland nevertheless went on to become president of the Supreme Court – and now also receives the title of distinguished alumnus at Aarhus University.

Perhaps it was just an embarrassing coincidence.

But you could be forgiven for thinking that the Danish legal system was literally trying to hold onto Jens Peter Christensen when he entered the courtroom as a judge for the first time back in 1999.

In any case, his black robes got well and truly stuck to the interior of the High Court of Western Denmark. First to the door handle on the way into the room, and later to the wheels under the judge’s chair, which lifted up with him when it was time to stand.

Jens Peter Christensen managed to wrestle himself free of the court room’s legal iron grip. And when he returned to his professor’s office at Aarhus University after his term as acting judge at the High Court, he closed the door behind him and swore he would never go back.

But, as the president of Denmark’s Supreme Court would be the first to admit, long-term career planning is not his style. As a former World Championship rower, he’s much more interested in focusing on the stroke he’s making right now. And then the next. And then the one after that.

Dreaming of a coalman career

“My father was a stoker, so he shovelled coal on the lowest decks of the ships across the Atlantic in the 1930s. That was the world I knew. I’ve been told that my earliest career aspiration was to be a coalman, delivering coal from house to house. Going around the neighbourhood with a large sack of coal on my back. That was my dream,” explains Jens Peter Christensen with one of his characteristic smiles.

“But my parents only stayed at school for seven years, and they were determined for me to have the opportunities they didn’t have. They never put pressure on me, but I enjoyed school, and they supported me. Early on, I apparently said to my mother that I wanted to stay at school for as long as I could. And that’s certainly how it turned out”.

Helped along by his competitive gene, which also came in handy in his local rowing club, Jens Peter Christensen went on to study at upper secondary school. And from there, it was clear that he would progress to university.

Not because he had a career plan – of course not. But because he had a thirst for knowledge and an awe-inspiring work ethic. Combined with his passion for sport and physiology, these attributes led to Jens Peter Christensen starting a medical degree in 1975.

“I don’t want to spend my day doing law”

It turned out, however, that there was one quality the hard-working student from Jutland did not possess: The ability to look at blood without fainting.

So he changed to economics, where he competed on grades with a certain Nina Smith, who went on to become a professor and economic adviser. But Jens Peter Christensen never really warmed to the subject, unlike when he discovered the degree programme in political science.

“I have no idea why I didn’t discover political science earlier. It introduced me to sociology, politics and history, and it was fascinating. Funnily enough, law was the only thing I wasn’t interested in. I deferred it for as long as I could, and when I couldn’t put it off any longer, I decided that I didn’t want to spend my day doing law. So I took an evening course instead, and that’s when I encountered my professional destiny,” explains Jens Peter Christensen.

This destiny came in the form of two teachers: the later law professor Gorm Toftegaard and associate professor Thomas Philbert. Outwardly, they were like oil and water. Toftegaard leaned across the table, filled the room with his booming voice, and criticised the students’ answers to his constitutional law questions, whereas Philbert was more friendly and stoic:

“But you could see that he found the whole subject exhilarating. He could stand there for three hours straight teaching administrative law. They were both extremely engaged in their subject. You could sense their passion. And it rubbed off on me”.

A law degree on an exemption

It’s safe to assume that very few presidents of the Supreme Court were rejected when they first applied to law school. And even fewer probably went on to complete their law degree without going to a single lecture.

But Jens Peter Christensen is not like most people. Neither was he when he applied to study law in the summer of 1990. At that point, he had a Master’s degree in political science and, having just submitted a PhD thesis on constitutional law, he was employed as an associate professor in the Department of Law at AU. All without having a law degree.

So he applied to study law, but he was rejected because he already had a degree at Master’s level:

“They kind of had to reject me. But by this point I had learned so much about law that I could see it was a bad decision. So I complained to the university. I didn’t get anywhere. So I complained again, but this time with a lengthier description of why I thought the university’s decision was, in my words, ‘inadequate, unreasonable and wrong’. Then they got fed up with me and gave me an exemption – perhaps as a form of revenge. Whatever their motivation, I now had to see it through. But I couldn’t go to lectures with the students I taught on my own course. So I bought the books and read from morning til night, whenever I got the chance”.

Jens Peter Christensen put the oars in the water. Disciplin. Concentration. One stroke at a time. And after a year and a half of reading – or 2,170 hours of independent study, to be exact – the law lecturer also had a Master of Laws.

Following the tiger into the jungle of rules

After this, Jens Peter Christensen wrote a higher doctoral dissertation on ministerial responsibility and became professor of public law at Aarhus University in 1998. This was where he planned to say – even after a successful term as acting judge in the High Court of Western Denmark, where the only blemish on his record was his inability to control his unruly robes on his first day in court.

“The university was just me. It really was. I loved the freedom and the opportunity to immerse myself in topics I found interesting. But I was encouraged to apply to the Supreme Court several times, and at one point my wife convinced me that I’d regret it if I said no again. Though she also said I’d probably get tired of it after three years. So I set about getting a three-year leave of absence from the university. After three years, I was still unsure, so I extended my leave for another two years, until I finally surrendered,” explains Jens Peter Christensen about his transition from professor to justice of the Supreme Court.

“As a judge, you lose the freedom you have as a university researcher. And you’re confronted with all sorts of things that you haven’t focused on before. At the Supreme Court, you cannot specialise. You get cases about everything under the sun. And you just have to get stuck into them. You don’t understand anything at first, but there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s like riding on a tiger’s back as it bounds into a jungle of rules, and you just have to hold on. If you fall off, it’s over. You have to know the material inside out. In every single case”.

Always connected to the university

Over the years, Jens Peter Christensen has seen the Danish legal system from the outside and the inside – and now also from above, as the president of the highest court in the country:

“Denmark has an incredibly good legal system, and the people of Denmark trust the system to get things right. I think this trust is completely justified. I continue to be impressed by the judges’ commitment to detail, professional pride and respect for the task at hand. There is a strong sense of responsibility and a tradition that resembles the university in many ways.”

Even though the Danish legal system eventually succeeded in clutching onto Jens Peter Christensen’s robes, there is no doubt that Aarhus University remains a meaningful part of his life:

“I always look up at my old balcony as I walk past Residence Hall 3 in the University Park. And I always say yes if I am asked to welcome first-semester students to their law degree. They may view this as an honour, but in reality it’s the other way round. It’s an honour for me. After all, the students are the university. They are the ones who bring new knowledge out into society. So it’s a privilege and a pleasure to help motivate them.

And what advice does the president of the Supreme Court give new students?

“Don’t plan too much. Just throw yourself into what you’re doing right now. You never know what it will lead to. Put your oars in the water and concentrate on the next stroke”.